Over the years, there has been much discussion of the classification of CP. Classification, or dividing into groups, is useful for a number of reasons. First, it provides information about the nature of the condition and its severity (its level or magnitude). Second, it allows us to learn from people who have the condition at a similar level.

A good measurement or classification system must be:

- Valid: It actually measures what it claims to measure.

- Reliable: It provides the same answer when used by different people or by the same person at different times.

- Accurate: It measures how close a value is to its true value. (An example would be how close an arrow gets to the target.)

- Precise: It measures how repeatable a measurement is. (An example would be how close the second arrow is to the first one, regardless of whether either is near the target.)

A kitchen scale (weighing scales) can be used to illustrate the different concepts:

- If the scale claims to measure weight and does so, then the scale is valid.

- If it provides the same reading regardless of who uses it or when they use it, then the scale is reliable.

- If the reading is correct when a known standardweight is weighed, then the scale is accurate.

- If repeated weighings of the same item give the same reading (whether accurate or not), then the scale is precise.

I will cover three main methods of classifying CP. These are based on:

- Topography: The area of the body affected

- Motor impairment: The type of motor disorder (a motor disorder affects the development of movement and posture)

- Gross motor function: The level of functional mobility

Classification of CP on the basis of topography

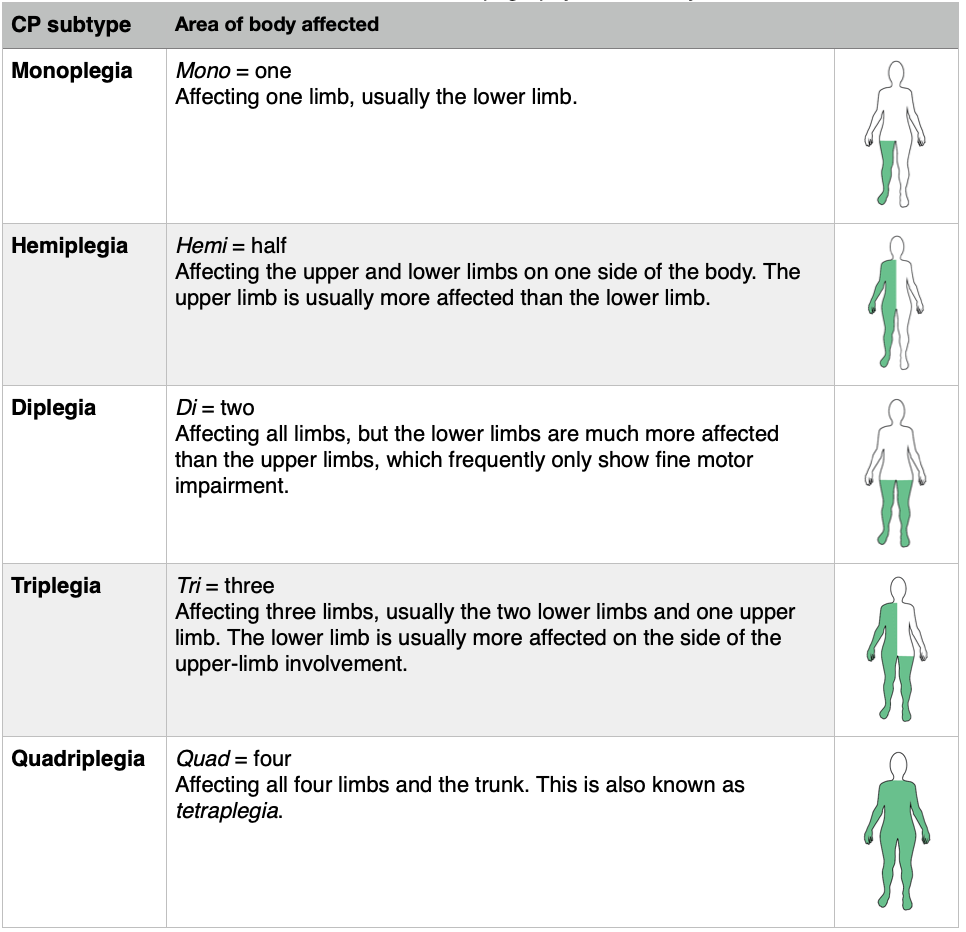

The historical method of classifying CP is on the basis of topography—the area of the body affected. The suffix “-plegia” is derived from the Greek word for stroke. The prefixes “mono-,” “hemi-,” “di-,” “tri-,” and “quad-,” again derived from the Greek or Latin words, indicate the area of the body affected. See table.

One of the disadvantages of this classification system is a lack of precision. However, this method of classifying CP has been and continues to be used extensively, particularly the terms hemiplegia, diplegia, and quadriplegia in the US.

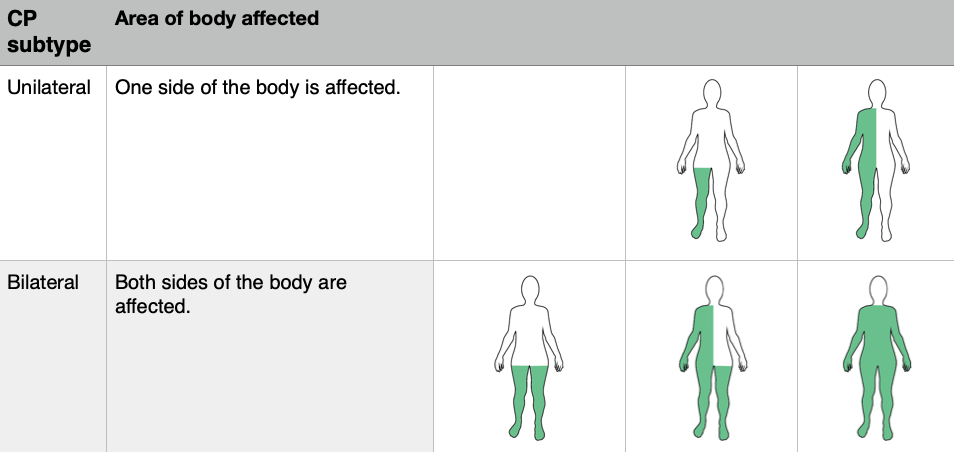

A recently adopted classification system, again based on topography, was adopted by the Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (SCPE) group. The SCPE’s classification system is thought to be reasonably reliable with room for improvement. It is now generally used in Europe and Australia. It identifies two main types of CP: unilateral and bilateral. See table.

Classification of CP on the basis of motor impairment

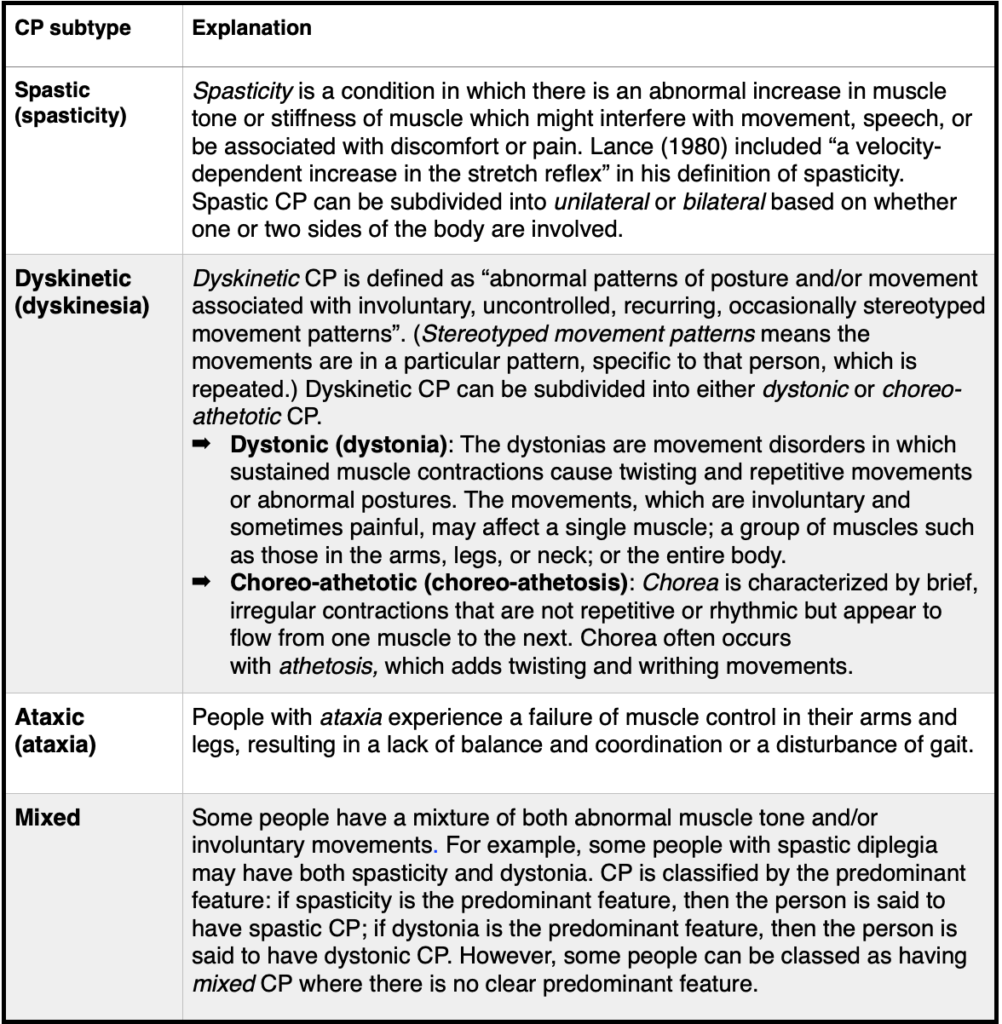

Another method classifies CP into subtypes based on the predominant features of the motor impairment. CP is characterized by abnormal muscle tone and problems with motor control which may or may not include involuntary movements. A brief explanation of the subtypes is included in the following table.

Most studies report that spasticity is the most common type of motor impairment, though the exact percentage varies. The general consensus is that 60 to 85 percent of those with CP have the spastic form. Only spastic CP is subdivided into bilateral or unilateral. This is because dyskinetic and ataxic CP generally affect the whole body.

A web link to a useful video titled “Types of CP” is included at the end.

Classification of CP on the basis of gross motor function

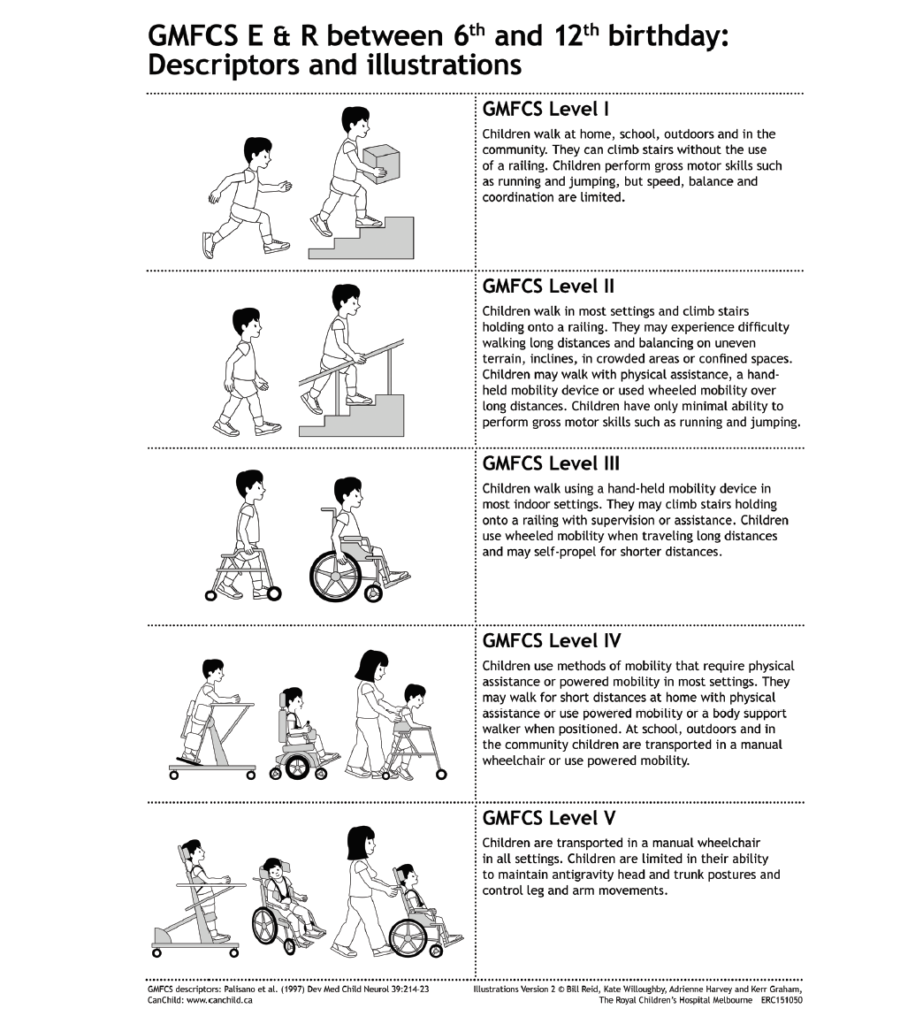

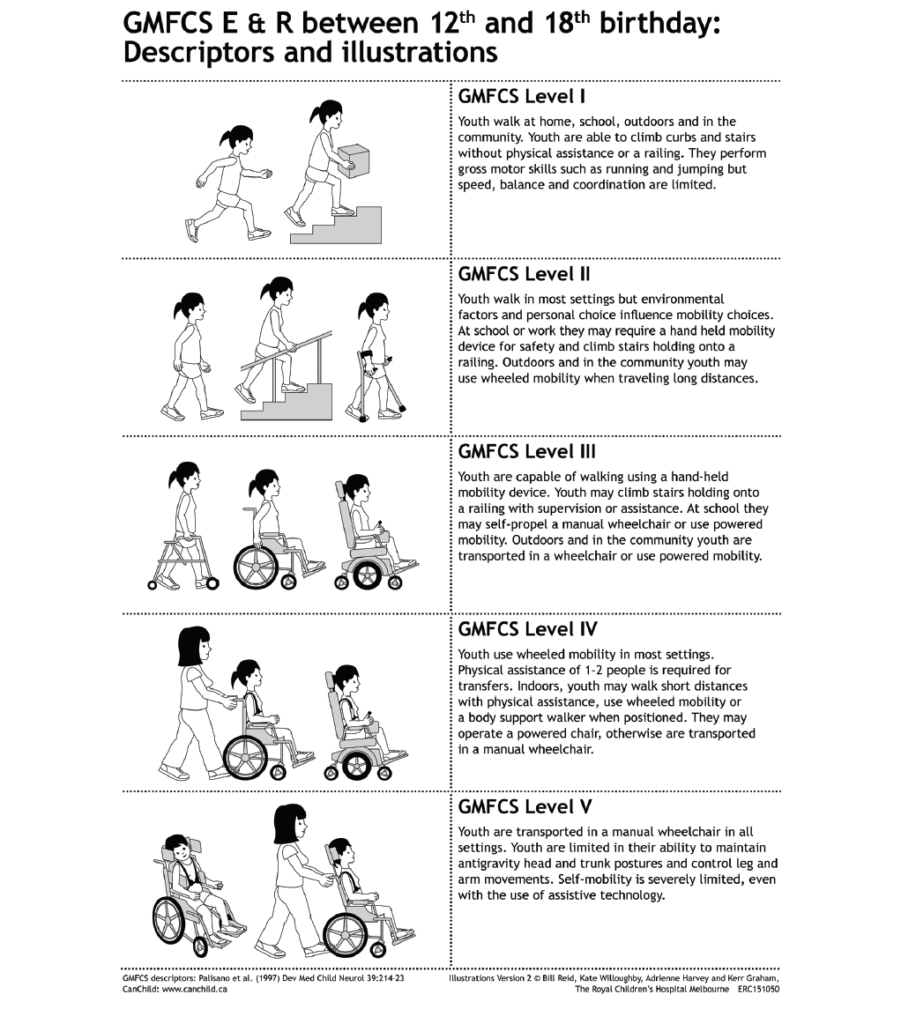

The final method of classifying CP is on the basis of gross motor function using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS). Gross motor function involves the movement of the arms, legs, and other large body parts.

The GMFCS is a five-level classification system that describes the functional mobility of children and adolescents with CP. It is based on how children and adolescents move on their own, with emphasis on sitting, transfers (moving from one position to another), and mobility. The GMFCS includes descriptions for five age groups: less than two years, two to four years, four to six years, six to 12 years, and 12 to 18 years. The emphasis is on the child/adolescent’s usual performance in their daily environment (i.e, their home and community). By choosing which description best matches the child at their current age, a child can be assigned a GMFCS level.

The following are descriptions of the five levels; these correspond to the method that best describes the child’s functional mobility after age six. Level I has the fewest movement limitations and level V has the greatest, thus the severity of the movement limitations increases with each increasing level. It is important to note, however, that the differences between the levels are not even.

- Level I Walks without limitations

- Level II Walks with limitations

- Level III Walks using a handheld mobility device

- Level IV Self-mobility with limitations; may use powered mobility

- Level V Transported in a manual wheelchair

Although the levels are based on the method of functional mobility that best describes the child’s performance after age six, a child can be classified much earlier using these descriptions.

The following summarizes the commencement of walking for children with CP at GMFCS levels I–III:

- At GMFCS level I, children walk between 18 months and 2 years without the need for any assistive mobility device. (Note that even at GMFCS level I, this is later than for typically developing children, as noted in the gross motor milestones.)

- At GMFCS level II, children aged 2 to 4 walk using an assistive mobility device as their preferred method of mobility. At ages 4 to 6, they walk without the need for a handheld mobility device indoors and for short distances on level surfaces outdoors.

- At GMFCS level III, children aged 2 to 4 may walk short distances indoors using a handheld mobility device (walker) and adult assistance for steering and turning. At ages 4 to 6, they walk with a handheld mobility device on level surfaces.

The full version of the GMFCS is a short document that contains very useful information. A web link to it is included at the end. The document contains further detail on mobility for each age and GMFCS level. It also includes a summary of the distinctions between each level to help determine the level that most closely resembles a particular child/adolescent’s current gross motor function. Web links to videos explaining the GMFCS are also included at the end.

The GMFCS has been proven to be relatively stable over time after age 2. A recent Swedish study provided further evidence of the stability of the GMFCS. Because the GMFCS level is stable, once a child’s GMFCS level is known, it offers insight into what the future may hold in terms of the child’s mobility. It helps answer some of the many questions we parents have in the early days, such as, “Will our child walk?” or, “How serious is their CP?”

It is important to note that just as a child’s diagnosis of spastic diplegia is generally stable throughout their life, their GMFCS level is generally stable. In other words, the area of the body affected and the severity of the condition (the GMFCS level) generally do not change.

Traditionally, medical professionals made the assessment, but the GMFCS Family Report Questionnaire (web link also included) now allows parents or the young person themself to do so. Professional and family reports have been shown to be consistent. Useful illustrations have been developed based on the GMFCS for the two upper age bands (six to 12 years and 12 to 18 years) by staff at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne.

The SCPE classified walking ability into three levels according to the GMFCS:

- Mild Independent walker; GMFCS levels I–II

- Moderate Walker with aid; GMFCS level III

- Severe Wheelchair; GMFCS levels IV–V

The GMFCS has been translated into many languages and is used all over the world. One of its many advantages is its simplicity. Though the GMFCS is now used in adulthood, particularly in research studies, it has not yet been validated for adults. Hopefully it will be. One study compared the GMFCS level of adults with CP with their GMFCS level at age 12 and found that GMFCS level observed around age 12 was highly predictive of motor function in adulthood.

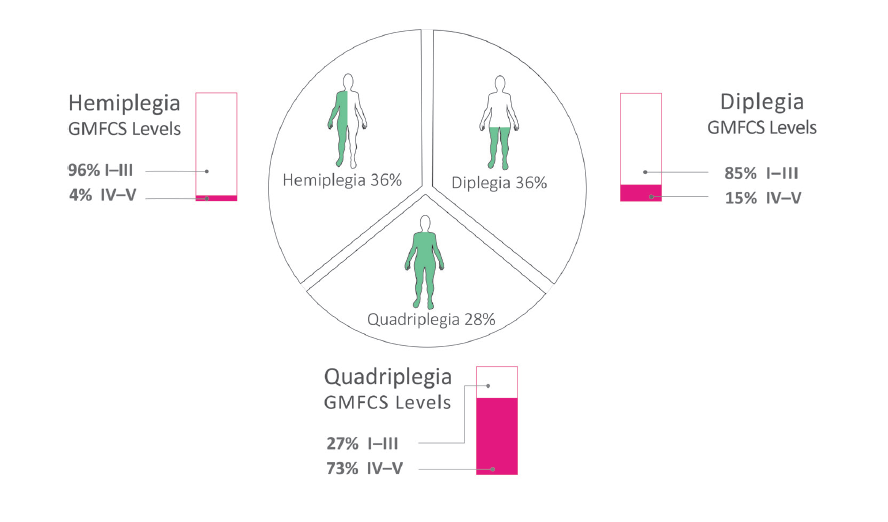

Let us now look at how individuals with spastic diplegia are distributed across the different GMFCS levels. The following diagram shows the proportion of children with CP by topography (area of the body affected) and gross motor function (GMFCS level) using data collated from five studies.

It shows that:

- 36 percent of people with CP had hemiplegia, 36 percent had diplegia, and 28 percent had quadriplegia.

- Of those with hemiplegia, 96 percent were at GMFCS levels I–III.

- Of those with diplegia, 85 percent were at GMFCS levels I–III.

- Of those with quadriplegia, 27 percent were at GMFCS levels I–III.

Thus this data shows that the majority of individuals with spastic diplegia were at GMFCS levels I–III.

As noted earlier, the SCPE subdivided spastic CP into unilateral or bilateral based on whether one or two sides of the body were involved. From the data above, one can broadly assume that:

- At GMFCS levels I–III, the majority of children with bilateral spastic CP have spastic diplegia.

- At GMFCS levels IV and V, the majority of children with bilateral spastic CP have spastic quadriplegia.

This explains why at GMFCS levels I–III the descriptors “spastic diplegia” and “bilateral spastic CP” (or simply “bilateral CP”) can largely be used interchangeably.

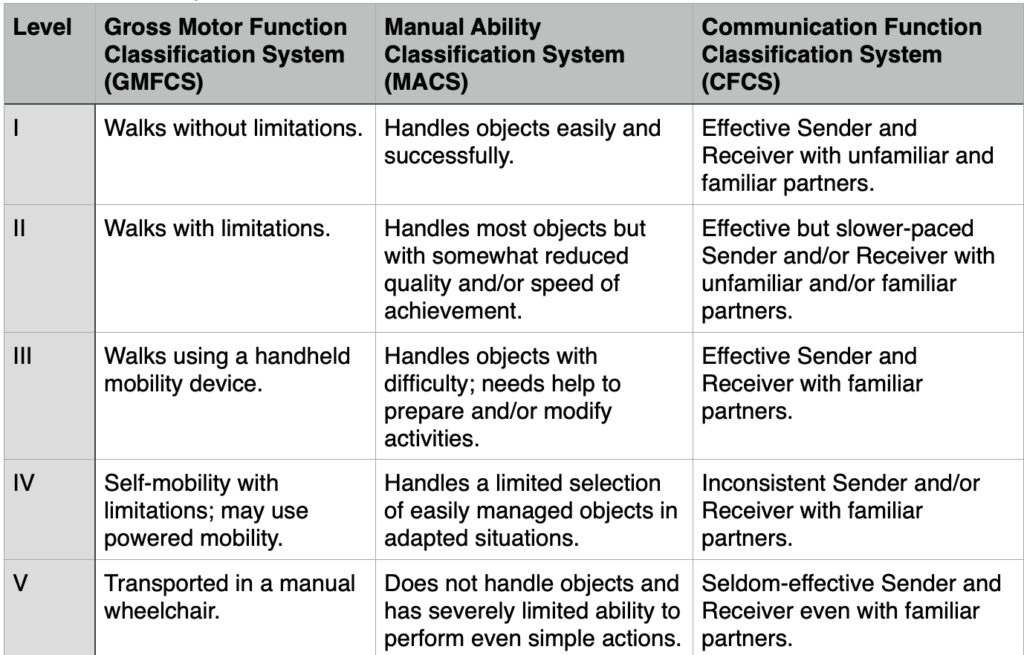

Classification systems similar to the GMFCS have since been developed for function in other areas:

- The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) is a five-level classification system that describes how children with CP aged four to 18 years use their hands to handle objects in daily activities. There is a separate Mini-MACS for children aged one to four.

- The Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) is a five-level classification system that describes everyday communication performance.

Web links to the MACS, Mini-MACS, and CFCS are included at the end. The following table summarizes the five levels of the three classification systems (GMFCS, MACS, and CFCS).

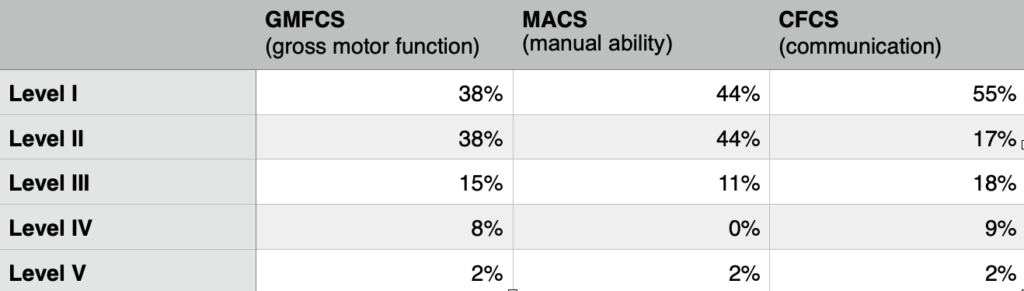

A study looked at the correlation between distribution of gross motor function, manual ability, and communication function. The following table shows the distribution for children and adolescents with spastic diplegia across the five levels of each classification (GMFCS, MACS, and CFCS).

It shows that in this study:

- 91 percent of children and adolescents with spastic diplegia were at GMFCS levels I–III.

- 99 percent of children and adolescents with spastic diplegia were at MACS levels I–III.

- 90 percent of children and adolescents with spastic diplegia were at CFCS levels I–II.

- The distribution across the three classification systems does not precisely correlate. For example, 38 percent of children and adolescents with spastic diplegia were at GMFCS level I, but 55 percent were at CFCS level I. This underscores the important point that the GMFCS does not predict functionality in domains other than mobility. (The same point applies to the MACS and the CFCS.)

Most children with spastic diplegia can be considered to have a mild or moderate (not severe) level of disability with regard to gross motor function (walking ability). Likewise, they can be considered to have a mild or moderate level of disability with regard to manual ability and communication.

We have now looked at the three main classification systems for CP. Of the three, only the GMFCS (and its offshoots, the MACS, Mini-MACS, and CFCS) has been proven to be valid and reliable.

Finally, it should be obvious from the information above that although CP is a single diagnosis, it is far from a uniform condition. Similar to autism, a name change from “cerebral palsy” to “cerebral palsy spectrum disorder” has recently been suggested.

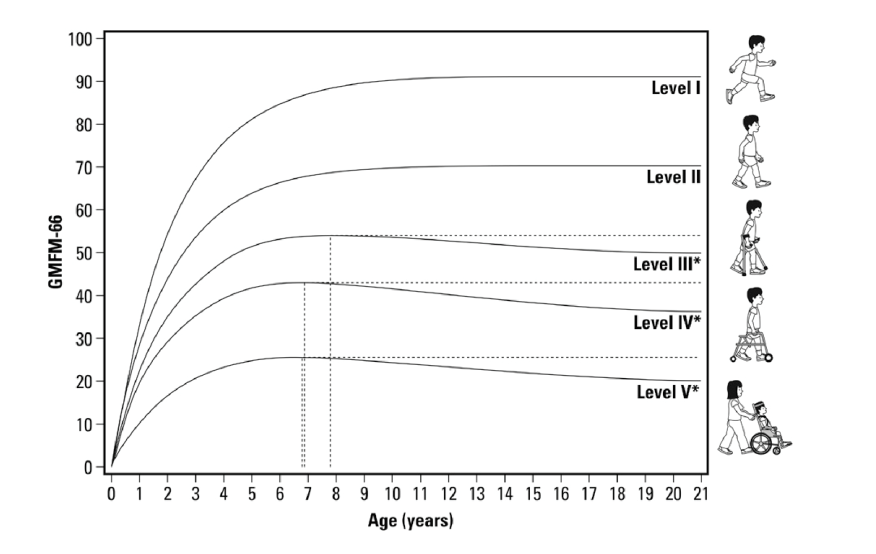

Gross motor development curves

The GMFCS led to the development of the gross motor development curves. The curves show the change in gross motor function over time as measured by the GMFM-66. There are five curves, one for each GMFCS level.

What do the curves show us?

- The curves represent the average GMFM-66 score (y-axis) at each GMFCS level by age (x-axis).

- For each GMFCS level there is an initial rapid rise in GMFM-66 score to a peak level, then the score plateaus (GMFCS levels I–II) or decreases (levels III–V).

- The GMFM-66 score (y-axis) is highest for level I and lowest for level V.

- The dotted lines show the timing of the peak in GMFM-66 score and the decrease from the peak to age 21 years for levels III–V.

- Even a child/adolescent at GMFCS level I does not reach 100, the maximum, on the GMFM-66 scale.

Why are the curves useful? They help answer some of the many questions we parents have in the early days. Knowing our child’s GMFCS level at age two, the curves allow us to see how our child’s gross motor function, as measured by the GMFM-66, is likely to develop over time.

The curves are based on averages, and while they are very useful, it is important to remember that some children were above and some below the line at each level. While remaining very realistic in our expectations, we should focus on helping our child reach their maximum possible gross motor function, not just hitting the average. The curves should guide, but not limit, our child’s potential.

My son Tommy was born in 1994. The first GMFCS to age 12 was published in 1997, and the curves were published in 2002. Looking back, I can see how useful they could have been earlier in Tommy’s life. Before these tools emerged, questions like, “Will our child walk?” were difficult for professionals to answer; they likely did not want to overpromise.

When I asked whether Tommy would walk, I was told he would walk before age seven but would likely need to use a wheelchair in college. As it turned out, Tommy began to walk independently just after his third birthday and continued to walk independently right through college. (In fact, my favorite photograph from his college graduation is one I took of the family and a friend walking to dinner that evening. It was special because not only was Tommy graduating, he was also walking unaided beside his dad and brothers. I sent a copy of that photograph, with great gratitude, to the many professionals who had treated him over the years.)

While I do not have a record of his earlier GMFM-66 scores, Tommy’s GMFM-66 score just before his 10th birthday was 78. Plotting that score on the curves put him between levels I and II, and at that time he was classed as level II (walks with limitations). This accurately describes how Tommy, now 25, walks today.

Useful web links

- Cerebral Palsy Alliance (2015) Types of Cerebral Palsy. (video)

- CanChild (2007) Gross Motor Function Classification System Expanded and Revised. (pdf)

- CanChild (2018) GMFCS Video. (video)

- Cerebral Palsy Foundation (n.d.) Insights from Experts: Motor Classification. (video)

- CanChild (2011) GMFCS Family Report Questionnaire. (pdf) (Scroll down to find separate sheets for each of the four age groups: 2–4, 4–6, 6–12, and 12–18.)

- MACS (2010) Manual Ability Classification System for Children with Cerebral Palsy 4–18 Years. (pdf)

- MACS (2013) Mini-Manual Ability Classification System for Children with Cerebral Palsy 1–4 Years of Age.(pdf)

- CFCS (2011) Communication Function Classification System (CFCS). [pdf]

The above is an extract from Spastic Diplegia–Bilateral Cerebral Palsy available here.